Is Matti Caspi really a genius or is it an exaggeration?

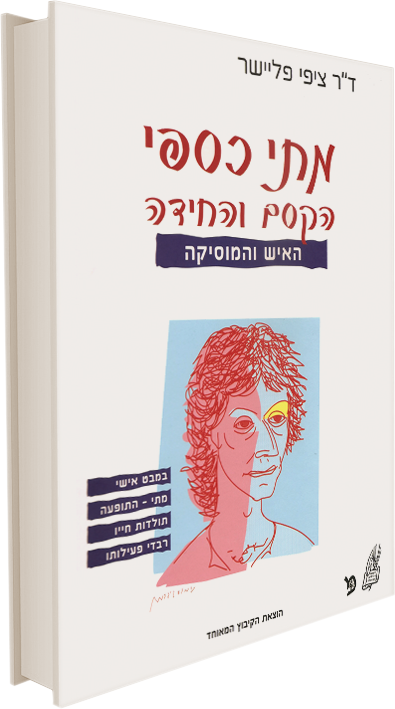

Musicologist Zippi Fleischer’s new book - “Matti Caspi - the Magic and the Riddle” is mainly designated to the fans of the composer and singer, who are interested in the inner mechanism of his perfect songs.

By Ben Shalev, “Haaretz”, February 31st, 2013

Matti Caspi gave an interview two years ago to “Haaretz” and told about the musicians who have influenced him the most, from Sasha Argov to Stevie Wonder and Antonio Carlos Jobim. “Until today, whenever I listen to his music it’s as if the sun shines upon me after it’s been cloudy and a bit cold” he said of Jobim. “Suddenly the sun comes out of the clouds and warms me up. Each time I listen as if it’s the first time and I’m filled with wonder again. How he did it. What a genius. He’s a genius. Jobim is a genius, just like Sasha was. Jobim is a genius”.

When the interview was over, I regretted not asking him the necessary question: “Do you think you’re also a genius”? but later on I changed my mind and was glad I didn’t ask him that. If he answered yes, he would have been portrayed as a braggart. If he answered no, he would have been portrayed as too naive. It’s not a fair question to be presented to an artist suspected to be a genius, moreover, in Caspi’s case the answer is clear.

Recently, published by “Hakibbutz Hameuchad”, “Matti Caspi - the Magic and the Riddle” the book about Matti Caspi’s musical creation by musicologist Zippi Fleischer came out to the shelves. “Matti Caspi is one of the geniuses of musical, historic and worldly creation” she writes. “He stands in the same row with Bach and Gershwin as the important mark makers of the development of the traditional harmonic language, on cardinal levels”.

That last statement is fundamentally wrong. The world outside of Israel doesn’t know Matti Caspi, which is why Caspi can’t have a far-spread worldly influence. And what about the bomb Fleischer drops in the first sentence (“One of the geniuses of musical, historic and worldly creation”)? The first instinct is to move in discomfort when hearing such a bombastic statement. It sounds like the mother of all exaggerations.

But wait, isn’t that what we all secretly think even when we listen to “You Took my Hand in Yours” for the two thousandth time? Or “Song of the Dove”? Or “Here Here”? Or “Someone”? Or “When God First Said”? And haven’t we all flirted with the idea that had Caspi been born in a different country or in a different time, he could’ve been considered to be one of the greatest composers of all time?

True, these are hypothetical stupid questions. And the question of genius doesn’t promote any true understanding. And Fleischer can’t really prove her extreme statement. Still, it’s good that she goes wild and makes that statement without fear. Because she says that when we listen to Caspi’s songs we are standing before the magnificence of creation: we are standing before an overwhelming musical perfection, aesthetically, emotionally and sensually.

“The Magic and the Riddle” is a book by a researcher who adores Caspi, just as this list was written by a journalist who adores him. It can be rightfully claimed that both lack a critical dimension, and of course, Caspi’s career, like any other artist’s, is worthy of a critical point of view. However, Fleischer doesn’t discuss Caspi’s career, but the songs that express the ”Matti Caspi nature” in its climax, and that nature, being perfect, needs no criticism.

“The Magic and the Riddle” is supposedly intended for the fans of Matti Caspi, and more specifically, for the composer’s / singer’s fans who are interested in the inner mechanism of his songs. For instance, “A Love Song (like a wheel)”. A while ago I hummed it to myself and was shocked to discover it has an entirely unanimous rhythmic pattern: the notes, from first to last, are placed in a pattern of pairs, maybe because it’s an intimate love song. Two by two they go by, like disciplined soldiers. But the absolute symmetry doesn’t put the song into a hard square splint. The melody is left breathing, free and dancing.

Fleischer mentions “Love Song” briefly. It isn’t one of the forty songs she analyses in her book, chord by chord. But the principal that exists in that song - a strict pattern which doesn’t contradict full freedom - is one of the basic principles of the “Matti Caspi” language according to her analysis. “Inside wonderfully solid patterns lies all the rhythmic and melodic richness, and the solid pattern allows the harmonic richness to flicker and go wild” writes Fleischer. “Only with this kind of frame can you develop unusual harmonic moves”.

Fleischer sees in Caspi a musical savage. “Matti’s musicality is animalistically wild, and it brings him to the point where he’s not afraid of anything - that’s why he’s so original” she writes. “He’s a very precise savage, and not less importantly: a dreamer savage. Spiritually and emotionally, I loved most of all the diving into the dream” writes Fleischer. “In every song I’ve found a dream. The songs are all, dreams first of all”. This impression expresses Fleischer’s combination of precise musical analysis and sensual listening which absorbs the heat and moist of the songs.

Caspi’s biography isn’t what the book is about, but we can’t help but mention a story from his childhood. In the early 50’s composer Mordechai Zaira used to visit the Hannita Kibbutz, where Caspi used to live, to work and vacation. One day when Zaira was playing the piano in the dining hall of the Kibbutz, 3 year old Matti stood beside him. “Would you like me to play for you”? asked Zaira and started to play “Little Yonathan”. “Not that way”! shouted Matti. Zaira asked who the boy’s mother was and when she arrived at the dining hall, Zaira told her: “You two would be idiot parents if you didn’t nurture and develop this talent. I don’t believe ‘Kibbutznicks’ (people raised in a Kibbutz). I have a boy his age - I’m taking him under my wing and train them both. When I make a human being out of him, then I’ll return him to you”.